Christology is the branch of Christian theology that reflects on the person and work of Jesus Christ—who he is, what he represents, and how he relates to God and humanity. It asks questions that have stirred hearts and minds for centuries: Was Jesus truly divine, truly human, or both? How do we understand his life, death, and resurrection? And what does it mean to call him the Son of God?

Early Christianity saw diverse and sometimes conflicting ideas about Christ’s identity. These ranged from views that emphasized his divinity to others that focused on his humanity. For example, Docetism claimed Jesus only appeared human and didn’t actually suffer, while Adoptionism argued that Jesus was a man elevated to divine status by God.

In response to such ideas, church leaders convened a series of councils to clarify doctrine. The Council of Nicaea in 325 CE confronted Arianism, which taught that Christ was a created being—not co-eternal with God. Nicaea rejected this and declared that the Son is "of the same substance" (homoousios) as the Father, laying the groundwork for orthodox Trinitarian belief.

The Christological debates didn’t stop there. The Council of Ephesus (431 CE) rejected Nestorianism, which emphasized a separation between Jesus' divine and human natures to the point that it seemed he was two persons. Instead, the council affirmed the unity of Christ’s person and upheld the title Theotokos (“God-bearer”) for Mary, affirming that she gave birth to the divine Word incarnate.

Soon after, Monophysitism (from Greek mono physis, "one nature") asserted that Christ had only one nature after the incarnation—either divine, or a composite of divine and human. The Council of Chalcedon (451 CE) responded by issuing a definition of Christ as one person in two natures, fully divine and fully human, “without confusion, without change, without division, without separation.” This Dyophysitism became the benchmark for orthodox Christology in both the Western and Eastern branches of Christianity.

However, not all Christian communities accepted these decisions. Some churches, like the Coptic Orthodox and Armenian Apostolic, rejected Chalcedon and developed their own Christological traditions, which are now considered part of Oriental Orthodoxy. These communities often embrace what they describe as Miaphysitism, a more nuanced alternative to Monophysitism that still affirms both the divinity and humanity of Christ within one united nature.

As Christian theology matured, thinkers like Athanasius, Cyril of Alexandria, and Augustine helped refine the Church’s understanding. In the Western tradition, reason and doctrinal clarity were key, while in the East, the mystery of the incarnation was often explored through liturgy and spiritual experience.

In modern theology, terms like high Christology (emphasizing Jesus’ divinity) and low Christology (emphasizing his humanity) help scholars analyze different emphases in scripture and tradition. There’s also kenotic Christology, based on Philippians 2:7, where Christ is said to have “emptied himself” to take on human form. This idea of divine self-limitation continues to inspire theological reflection today.

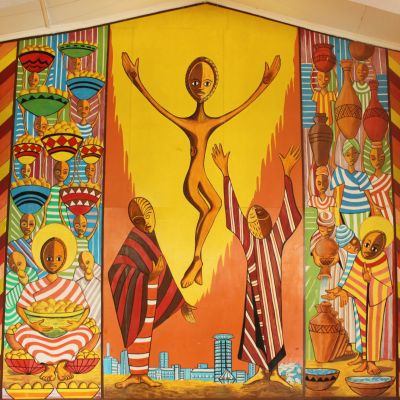

Throughout history, beliefs labeled as "heresies" were often genuine attempts to solve the mysteries surrounding Christ’s identity. While many were rejected, they contributed to the evolving dialogue. Today, Christology remains a vibrant field—engaging not only ancient doctrines but new developments like feminist, liberation, and postcolonial Christologies that reinterpret Jesus through the lens of justice, marginalization, culture, diversity, and lived experience.

Whether through scholarly study or spiritual contemplation, many continue to ask: Who is Jesus, and why does he matter?

Further Reading

- Ayres, Lewis. Nicaea and Its Legacy: An Approach to Fourth-Century Trinitarian Theology. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- González, Justo L. The Story of Christianity, Volume 1: The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation. HarperOne, 2010.

- Grillmeier, Aloys. Christ in Christian Tradition, Volume 1: From the Apostolic Age to Chalcedon (451). Westminster John Knox Press, 1975.

- Kelly, J. N. D. Early Christian Doctrines. HarperOne, 1978.

- McGrath, Alister E. Christian Theology: An Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell, 2016.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav. The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine, Volume 1: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100–600). University of Chicago Press, 1971.

- Richardson, Alan (ed.). A Theological Word Book of the Bible. SCM Press, 1950.

- Young, Frances M. From Nicaea to Chalcedon: A Guide to the Literature and Its Background. SCM Press, 1983.

Comments