|

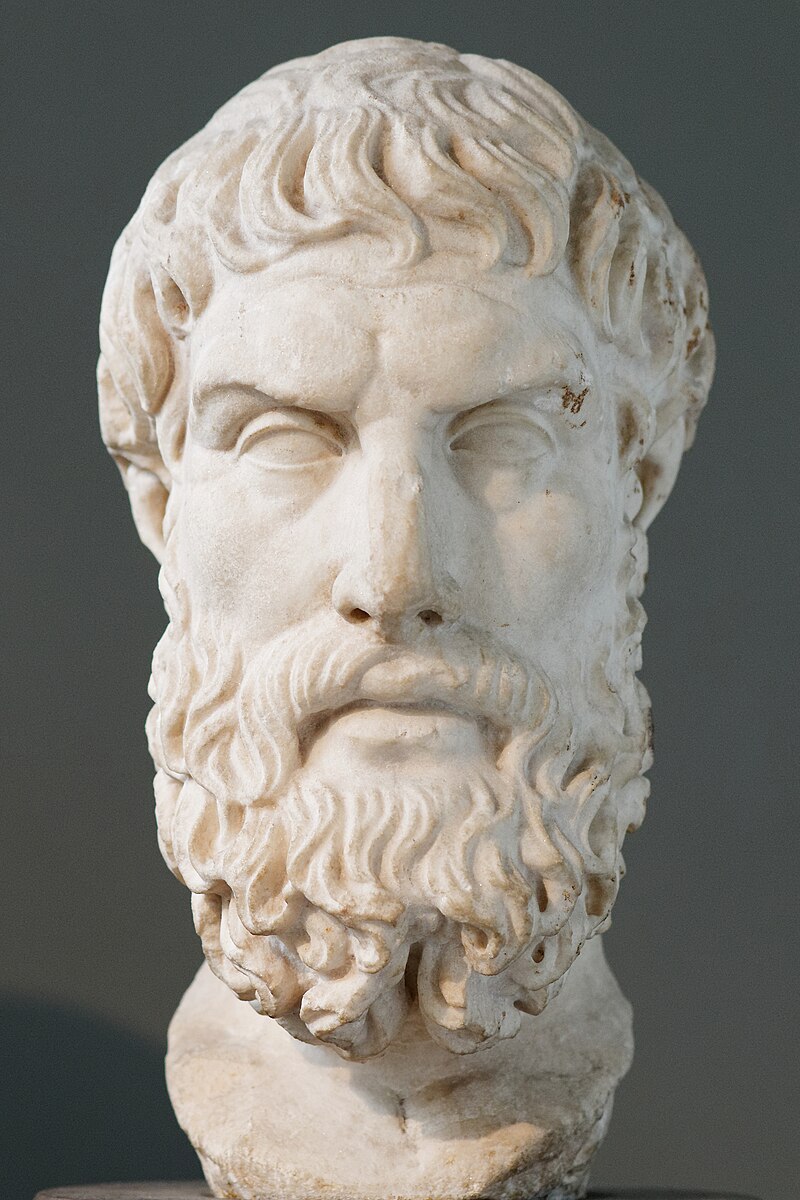

| Epicurus, founder of the Epicurean school. Roman copy after a lost Hellenistic original. |

Epicureanism, founded by the Greek philosopher Epicurus in the 4th century BCE and flourishing well into the 3rd century CE, is often wildly misunderstood. Far from a “party-all-the-time” doctrine, this ancient philosophy centers on tranquility (ataraxia) and freedom from pain (aponia), not overindulgence.

While the pursuit of personal happiness is central, Epicureanism emphasizes a kind of happiness born of clarity, simplicity, and inner peace—not of excess. This key distinction has been blurred for centuries. Although medieval Christian critics certainly played a role in misrepresenting Epicurean thought—often portraying it as immoral or godless—this distortion began much earlier, especially with Roman thinkers like Cicero and Plutarch. These critics frequently painted Epicurus as a hedonist in the basest sense. Later Christian theologians, such as Augustine, inherited these caricatures and often relied on secondhand sources, rarely engaging directly with Epicurus’ actual writings.

Epicurus distinguished between physical and mental pleasures, elevating the latter as deeper and longer-lasting. Mental pleasures span past, present, and future: relishing a memory, enjoying present peace of mind, or anticipating a joyful event. These are the pleasures that build true contentment.

Even more crucial was friendship (philia). Epicurus believed close, trusting relationships were essential for attaining lasting tranquility. A simple meal shared with friends, he taught, was more pleasurable and meaningful than any extravagant feast taken alone. Community, warmth, and sincerity—these were the nutrients of the Epicurean life.

|

| Epicurus depicted in the Nuremberg Chronicle |

A Material Cosmos, Without Fear

Epicurus’ worldview was deeply materialistic, yet strikingly serene. He adopted the atomism of Democritus, holding that all reality consists of indestructible atoms moving through the void. This proto-scientific model dismissed divine causality: natural events occur due to natural causes, not supernatural interference.

Epicurus did acknowledge the existence of gods—but not as personal deities who meddle in human affairs. He imagined them as immortal, blissful beings made of subtler matter, residing in serene detachment. As such, they are not to be feared or worshipped for favor. This was not atheism, but rather a radical redefinition of divinity.

Epicurus also rejected Plato’s metaphysical Forms and the idea of an immortal soul. For him, death is the end of consciousness, and thus, not something to dread. “When we are, death is not; when death is, we are not,” he famously wrote.

The Garden: Radical Inclusion

Epicurus established his school in Athens, calling it The Garden. More than a place of learning, it was a living embodiment of his values: inclusion, simplicity, and calm reflection. Remarkably for its time, The Garden welcomed women, slaves, and people of all social ranks—a radical stance in a deeply hierarchical society.

This openness was philosophical as well as social. Epicurus taught that anyone—regardless of background—could cultivate wisdom and attain happiness. In this community, pleasures were not purchased but discovered in simplicity, moderation, and shared insight.

He distinguished among three types of desire:

- Natural and necessary (e.g., food, shelter, friendship)

- Natural but unnecessary (e.g., luxury)

- Vain and empty (e.g., power, fame, immortality)

By satisfying only what is natural and necessary, one avoids anxiety, frustration, and illusion.

The Tetrapharmakos – Fourfold Cure

The Tetrapharmakos ("four-part cure") offers a concise summary of Epicurean ethics—practical, portable, and psychologically insightful:

- Don’t fear God – The gods are real but indifferent to us.

- Don’t worry about death – Death ends sensation; there's nothing to experience or fear.

- What is good is easy to obtain – Simple, natural pleasures are readily accessible.

- What is terrible is easy to endure – Intense pain is usually brief; chronic pain, if mild, can be offset by mental peace.

Though this formula appeared in later Epicurean texts rather than from Epicurus directly, it faithfully captures the spirit of his teaching.

"French wine-tasters," according to Copilot

Misunderstood Then, Misunderstood Now

Modern culture often equates Epicureanism with refined indulgence—fine wines, gourmet food, curated travel. While these can be part of a good life, they are not its foundation. Epicureanism is less about adding pleasures and more about subtracting anxieties. Its real genius lies in teaching how to want less, how to live more consciously, and how to find depth in simplicity.

Contemporary psychological insights—including mindfulness practices, CBT, and stoic resilience training—have remarkable parallels to Epicurean methods. Like Epicurus, modern therapists often urge people to shift their focus away from imagined threats and toward present-moment awareness and gratitude. Some scholars have compared Epicurus to a proto-therapist or practical psychologist, offering tools for mental and emotional regulation centuries before modern science emerged.

Still, as compelling as this worldview is for some, it doesn’t resonate with everyone. For those of us with a spiritual worldview, Epicureanism can feel incomplete. Even concepts like Zen-like "mindfulness" just don't cut it when you have reason to believe in God.

I remember debating these ideas in my youth. A friend once challenged me:

“What if all this spiritual stuff isn’t real? You’ll have wasted your whole life believing in something that isn’t true!”

Without hesitation, I replied:

“It gives me meaning.”

Decades later, I stand by that answer. Spirituality not only gives me meaning but has transformed my entire understanding of why we're here and what we should be trying to do.

Comments